A book is an object recording information in the form of printed writing or images. Modern books are typically in codex format, composed of many pages bound together and protected by a cover. Older formats include the scroll and the tablet. The term is sometimes used in contrast to periodical literature, such as newspapers or magazines, where new editions are published according to a regular schedule. The book publishing process is the series of steps involved in their creation and dissemination.

As a conceptual object, a book refers to a written work of substantial length, which may be distributed either physically or digitally as an electronic book (ebook). These works can be broadly classified into fiction (containing invented content, often narratives) and non-fiction (containing content intended as factual truth). A physical book may not contain such a work: for example, it may contain only drawings, engravings, photographs, puzzles, or removable content like paper dolls. It may also be left empty for personal use, as in the case of account books, appointment books, autograph books, notebooks, diaries and sketchbooks.

Books are sold at both regular stores and specialized bookstores, as well as online for delivery, and can be borrowed from libraries. The reception of books has led to a number of social consequences, including censorship.

The modern book industry has seen several major changes due to new technologies, including ebooks and audiobooks (recordings of books being read aloud). Awareness of the needs of print-disabled people has led to a rise in formats designed for greater accessibility, such as braille printing and large-print editions. Google Books estimated in 2010 that approximately 130 million total unique books had been published.

Etymology

The word book comes from the Old English bōc, which in turn likely comes from the Germanic root *bōk-, cognate to “beech“.[1] In Slavic languages like Russian, Bulgarian, Macedonian буква bukva—”letter” is cognate with “beech”. In Russian, Serbian and Macedonian, the word букварь (bukvar’) or буквар (bukvar) refers to a primary school textbook that helps young children master the techniques of reading and writing. It is thus conjectured that the earliest Indo-European writings may have been carved on beech wood.[2] The Latin word codex, meaning a book in the modern sense (bound and with separate leaves), originally meant “block of wood”.[3]

An avid reader or collector of books is a bibliophile, or colloquially a “bookworm“.[4]

Definitions

In its modern incarnation, a book is typically composed of many pages (commonly of paper, parchment, or vellum) that are bound together along one edge and protected by a cover. By extension, book refers to a physical book’s written, printed, or graphic contents.[5] A single part or division of a longer written work may also be called a book, especially for some works composed in antiquity: each part of Aristotle‘s Physics, for example, is a book.[6]

It is difficult to create a precise definition of the book that clearly delineates it from other kinds of written material across time and culture. The meaning of the term has changed substantially over time with the evolution of communication media.[7] Historian of books James Raven has suggested that when studying how books have been used to communicate, they should be defined in a broadly inclusive way as “portable, durable, replicable and legible” means of recording and disseminating information, rather than relying on physical or contextual features. This would include, for example, ebooks, newspapers, and quipus (a form of knot-based recording historically used by cultures in Andean South America), but not objects fixed in place such as inscribed monuments.[8][9]

A stricter definition is given by UNESCO: for the purpose of recording national statistics on book production, it recommended that a book be defined as “a non-periodical printed publication of at least 49 pages, exclusive of the cover pages, published in the country and made available to the public”, distinguishing them from other written material such as pamphlets.[5][10] Kovač et al. have critiqued this definition for failing to account for new digital formats. They propose four criteria (a minimum length; textual content; a form with defined boundaries; and “information architecture” like linear structure and certain textual elements) that form a “hierarchy of the book”, in which formats that fulfill more criteria are considered more similar to the traditional printed book.[11][12]

Although in academic language a monograph is a specialist work on a single subject, in library and information science the term is used more broadly to mean any non-serial publication complete in one volume (a physical book) or a definite number of volumes (such as a multi-volume novel), in contrast to serial or periodical publications.[13][6]

History

Main article: History of books

The history of books became an acknowledged academic discipline in the 1980s. Contributions to the field have come from textual scholarship, codicology, bibliography, philology, palaeography, art history, social history and cultural history. It aims to demonstrate that the book as an object, not just the text contained within it, is a conduit of interaction between readers and words. Analysis of each component part of the book can reveal its purpose, where and how it was kept, who read it, ideological and religious beliefs of the period, and whether readers interacted with the text within. Even a lack of such evidence can leave valuable clues about the nature of a particular book.

The earliest forms of writing were etched on tablets, transitioning to palm leaves and papyrus in ancient times. Parchment and paper later emerged as important substrates for bookmaking, introducing greater durability and accessibility.[14] Across regions like China, the Middle East, Europe, and South Asia, diverse methods of book production evolved. The Middle Ages saw the rise of illuminated manuscripts, intricately blending text and imagery, particularly during the Mughal era in South Asia under the patronage of rulers like Akbar and Shah Jahan.[15][16]

Prior to the invention of the printing press in the 15th century, made famous by the Gutenberg Bible, each text was a unique handcrafted valuable article, personalized through the design features incorporated by the scribe, owner, bookbinder, and illustrator.[17] Its creation marked a pivotal moment for book production. Innovations like movable type and steam-powered presses accelerated manufacturing processes and contributed to increased literacy rates. Copyright protection also emerged, securing authors’ rights and shaping the publishing landscape.[18] The Late Modern Period introduced chapbooks, catering to a wider range of readers, and mechanization of the printing process further enhanced efficiency.

The 20th century witnessed the advent of typewriters, computers, and desktop publishing, transforming document creation and printing. Digital advancements in the 21st century led to the rise of ebooks, propelled by the popularity of ereaders and accessibility features. While discussions about the potential decline of physical books have surfaced, print media has proven remarkably resilient, continuing to thrive as a multi-billion dollar industry.[19] Additionally, efforts to make literature more inclusive emerged, with the development of Braille for the visually impaired and the creation of spoken books, providing alternative ways for individuals to access and enjoy literature.[20]

Tablet

Main articles: Clay tablet and Wax tablet

Some of the earliest written records were made on tablets. Clay tablets (flattened pieces of clay impressed with a stylus) were used in the Ancient Near East throughout the Bronze Age and well into the Iron Age, especially for writing in cuneiform. Wax tablets (pieces of wood covered in a layer of wax) were used in classical antiquity and throughout the Middle Ages.

The custom of binding several wax tablets together (Roman pugillares) is a possible precursor of modern bound books.[21] The etymology of the word codex (block of wood) suggests that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets.[22]

Scroll

Main article: Scroll

Scrolls made from papyrus were first used for writing in Ancient Egypt, perhaps as early as the First Dynasty, although the earliest evidence is from the account books of King Neferirkare Kakai of the Fifth Dynasty (about 2400 BC). According to Herodotus (History 5:58), the Phoenicians brought writing and papyrus to Greece around the 10th or 9th century BC. Whether made from papyrus, parchment, or paper, scrolls were the dominant writing medium in the Hellenistic, Roman, Chinese, Hebrew, and Macedonian cultures. The codex dominated in the Roman world by late antiquity, but scrolls persisted much longer in Asia.[citation needed]

Codex

Main article: Codex

The codex is the ancestor of the modern book, consisting of sheets of uniform size bound along one edge and typically held between two covers made of some more robust material. Isidore of Seville (died 636) explained the then-current relation between a codex, book, and scroll in his Etymologiae (VI.13): “A codex is composed of many books; a book is of one scroll. It is called codex by way of metaphor from the trunks (codex) of trees or vines, as if it were a wooden stock, because it contains in itself a multitude of books, as it were of branches”.

The first written mention of the codex as a form of book is from Martial, in his Apophoreta CLXXXIV at the end of the first century, where he praises its compactness. However, the codex never gained much popularity in the pagan Hellenistic world, and only within the Christian community did it gain widespread use.[23] This change happened gradually during the 3rd and 4th centuries, and the reasons for adopting the codex form of the book were several: the format was more economical than the scroll, as both sides of the writing material can be used; and it was portable, searchable, and easier to conceal. The Christian authors may also have wanted to distinguish their writings from the pagan and Judaic texts written on scrolls.

The codices of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica had the same form as the European codex, but were instead made with long folded strips of either fig bark (amatl) or plant fibers, often with a layer of whitewash applied before writing. New World codices were written as late as the 16th century (see Maya codices and Aztec codices). Those written before the Spanish conquests seem all to have been single long sheets folded concertina-style, sometimes written on both sides of the local amatl paper.

Manuscript

Main article: Manuscript

See also: Palm-leaf manuscript

Manuscripts, handwritten and hand-copied documents, were the only form of writing before the invention and widespread adoption of print. Advances were made in the techniques used to create them.

In the early Western Roman Empire, monasteries continued Latin writing traditions related to Christianity, and the clergy were the predominant readers and copyists. The bookmaking process was long and laborious. They were usually written on parchment or vellum, writing surfaces made from processed animal skin. The parchment had to be prepared, then the unbound pages were planned and ruled with a blunt tool or lead, after which the text was written by a scribe, who usually left blank areas for illustration and rubrication. Finally, it was bound by a bookbinder.[24]

Because of the difficulties involved in making and copying books, they were expensive and rare. Smaller monasteries usually had only a few dozen books. By the 9th century, larger collections held around 500 volumes and even at the end of the Middle Ages, the papal library in Avignon and Paris library of the Sorbonne held only around 2,000 volumes.[25]

The rise of universities in the 13th century led to an increased demand for books, and a new system for copying appeared. The books were divided into unbound leaves (pecia), which were lent out to different copyists, so the speed of book production was considerably increased. The system was maintained by secular stationers guilds, which produced both religious and non-religious material.[26]

In India, bound manuscripts made of birch bark or palm leaf had existed since antiquity.[27] The text in palm leaf manuscripts was inscribed with a knife pen on rectangular cut and cured palm leaf sheets; coloring was then applied to the surface and wiped off, leaving the ink in the incised grooves. Each sheet typically had a hole through which a string could pass, and with these the sheets were tied together with a string to bind like a book.

Woodblock printing

Main article: Woodblock printing

In woodblock printing, a relief image of an entire page is carved into blocks of wood, inked, and used to print copies of that page. It originated in the Han dynasty before 220 AD, used to print textiles and later paper, and was widely used throughout East Asia. The oldest dated book printed by this method is The Diamond Sutra (868 AD). The method (called woodcut when used in art) arrived in Europe in the early 14th century. Books (known as block-books), as well as playing-cards and religious pictures, began to be produced by this method. Creating an entire book was a painstaking process, requiring a hand-carved block for each page, and the wooden blocks could crack if stored for too long.

Movable type and incunabula

Main articles: Movable type and Incunable

The Chinese inventor Bi Sheng made movable type of earthenware c. 1045, but there are no known surviving examples of his printing. Around 1450, Johannes Gutenberg independently invented movable type in Europe, along with innovations in casting the type based on a matrix and hand mould. This invention gradually made books less expensive to produce and more widely available. Early printed books, single sheets and images which were created before 1501 in Europe are known as incunables or incunabula.[28]

19th century to present

Steam-powered printing presses became popular in the early 19th century. These machines could print 1,100 sheets per hour,[29] but workers could only set 2,000 letters per hour.[citation needed] Monotype and linotype typesetting machines were introduced in the late 19th century. They could set more than 6,000 letters per hour and an entire line of type at once. There have been numerous improvements in the printing press. In mid-20th century, European book production had risen to over 200,000 titles per year.

During the 20th century, libraries faced an ever-increasing rate of publishing, sometimes called an information explosion. The advent of electronic publishing and the internet means that new information is often published online rather than in printed books, for example through a digital library. “Print on demand” technologies, which make it possible to print as few as one book at a time, have made self-publishing (and vanity publishing) much easier and more affordable, and has allowed publishers to keep low-selling books in print rather than declaring them out of print.

Contemporary publishing

Main article: Publishing

Presently, books are typically produced by a publishing company in order to be put on the market by distributors and bookstores. The publisher negotiates a formal legal agreement with authors in order to obtain the copyright to works, then arranges for them to be produced and sold. The major steps of the publishing process are: editing and proofreading the work to be published; designing the printed book; manufacturing the books; and selling the books, including marketing and promotion. Each of these steps is usually taken on by third-party companies paid by the publisher.[30] This is in contrast to self-publishing, where an author pays for the production and distribution of their own work and manages some or all steps of the publishing process.[31]

English-language publishing is currently dominated by the so-called “Big Five” publishers: Penguin Random House, Hachette Book Group, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, and Macmillan Publishers. They were estimated to make up almost 60 percent of the market for general-readership books in 2021.[32]

Design

Main article: Book design

Book design is the art of incorporating the content, style, format, design, and sequence of the various elements of a book into a coherent unit.[33]

Layout

See also: Page layout

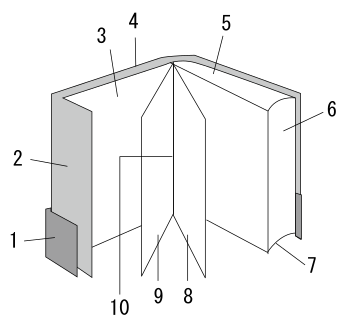

Modern books are organized according to a particular format called the book’s layout. Although there is great variation in layout, modern books tend to adhere to a set of rules with regard to what the parts of the layout are and what their content usually includes. A basic layout will include a front cover, a back cover and the book’s content which is called its body copy or content pages. The front cover often bears the book’s title (and subtitle, if any) and the name of its author or editor(s). The inside front cover page is usually left blank in both hardcover and paperback books. The next section, if present, is the book’s front matter, which includes all textual material after the front cover but not part of the book’s content such as a foreword, a dedication, a table of contents and publisher data such as the book’s edition or printing number and place of publication. Between the body copy and the back cover goes the end matter which would include any indices, sets of tables, diagrams, glossaries or lists of cited works (though an edited book with several authors usually places cited works at the end of each authored chapter). The inside back cover page, like that inside the front cover, is usually blank. The back cover is the usual place for the book’s ISBN and maybe a photograph of the author(s)/ editor(s), perhaps with a short introduction to them. Also here often appear plot summaries, barcodes and excerpted reviews of the book.[34]

The body of the books is usually divided into parts, chapters, sections and sometimes subsections that are composed of at least a paragraph or more.

Size

Main article: Book size

The size of a book is generally measured by the height against the width of a leaf, or sometimes the height and width of its cover.[35] A series of terms commonly used by contemporary libraries and publishers for the general sizes of modern books ranges from folio (the largest), to quarto (smaller) and octavo (still smaller). Historically, these terms referred to the format of the book, a technical term used by printers and bibliographers to indicate the size of a leaf in terms of the size of the original sheet. For example, a quarto was a book printed on sheets of paper folded in half twice, with the first fold at right angles to the second, to produce 4 leaves (or 8 pages), each leaf one fourth the size of the original sheet printed – note that a leaf refers to the single piece of paper, whereas a page is one side of a leaf. Because the actual format of many modern books cannot be determined from examination of the books, bibliographers may not use these terms in scholarly descriptions.

Illustration

Main article: Book illustration

While some form of book illustration has existed since the invention of writing, the modern Western tradition of illustration began with 15th-century block books, in which the book’s text and images were cut into the same block.[36] Techniques such as engraving, etching, and lithography have also been influential.

Manufacturing

The methods used for the printing and binding of books continued fundamentally unchanged from the 15th century into the early 20th century. While there was more mechanization, a book printer in 1900 still used movable metal type assembled into words, lines, and pages to create copies. Modern paper books are printed on paper designed specifically for printing. Traditionally, book papers are off-white or low-white papers (easier to read), are opaque to minimize the show-through of text from one side of the page to the other and are (usually) made to tighter caliper or thickness specifications, particularly for case-bound books. Different paper qualities are used depending on the type of book: Machine finished coated papers, woodfree uncoated papers, coated fine papers and special fine papers are common paper grades.

Today, the majority of books are printed by offset lithography.[37] When a book is printed, the pages are laid out on the plate so that after the printed sheet is folded the pages will be in the correct sequence. Books tend to be manufactured nowadays in a few standard sizes. The sizes of books are usually specified as “trim size”: the size of the page after the sheet has been folded and trimmed. The standard sizes result from sheet sizes (therefore machine sizes) which became popular 200 or 300 years ago, and have come to dominate the industry. British conventions in this regard prevail throughout the English-speaking world, except for the US. The European book manufacturing industry works to a completely different set of standards.

Hardcover books have a stiff binding, while paperback books have cheaper, flexible covers which tend to be less durable. Publishers may produce low-cost pre-publication copies known as galleys or “bound proofs” for promotional purposes, such as generating reviews in advance of publication. Galleys are usually made as cheaply as possible, since they are not intended for sale.

Printing

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Some books, particularly those with shorter runs (i.e. with fewer copies) will be printed on sheet-fed offset presses, but most books are now printed on web presses, which are fed by a continuous roll of paper, and can consequently print more copies in a shorter time. As the production line circulates, a complete “book” is collected together in one stack of pages, and another machine carries out the folding, pleating, and stitching of the pages into bundles of signatures (sections of pages) ready to go into the gathering line. The pages of a book are printed two at a time, not as one complete book. Excess numbers are printed to make up for any spoilage due to make-readies or test pages to assure final print quality.

A make-ready is the preparatory work carried out by the pressmen to get the printing press up to the required quality of impression. Included in make-ready is the time taken to mount the plate onto the machine, clean up any mess from the previous job, and get the press up to speed. As soon as the pressman decides that the printing is correct, all the make-ready sheets will be discarded, and the press will start making books. Similar make readies take place in the folding and binding areas, each involving spoilage of paper.

Recent developments in book manufacturing include the development of digital printing. Book pages are printed, in much the same way as an office copier works, using toner rather than ink. Each book is printed in one pass, not as separate signatures. Digital printing has permitted the manufacture of much smaller quantities than offset, in part because of the absence of make readies and of spoilage. Digital printing has opened up the possibility of print-on-demand, where no books are printed until after an order is received from a customer.

Binding

Main article: Bookbinding

After the signatures are folded and gathered, they move into the bindery. In the middle of last century there were still many trade binders—stand-alone binding companies which did no printing, specializing in binding alone. At that time, because of the dominance of letterpress printing, typesetting and printing took place in one location, and binding in a different factory. When type was all metal, a typical book’s worth of type would be bulky, fragile and heavy. The less it was moved in this condition the better: so printing would be carried out in the same location as the typesetting. Printed sheets on the other hand could easily be moved. Now, because of increasing computerization of preparing a book for the printer, the typesetting part of the job has flowed upstream, where it is done either by separately contracting companies working for the publisher, by the publishers themselves, or even by the authors. Mergers in the book manufacturing industry mean that it is now unusual to find a bindery which is not also involved in book printing (and vice versa).

If the book is a hardback its path through the bindery will involve more points of activity than if it is a paperback. Unsewn binding is now increasingly common. The signatures of a book can also be held together by “Smyth sewing” using needles, “McCain sewing”, using drilled holes often used in schoolbook binding, or “notch binding”, where gashes about an inch long are made at intervals through the fold in the spine of each signature. The rest of the binding process is similar in all instances. Sewn and notch bound books can be bound as either hardbacks or paperbacks.

Finishing

“Making cases” happens off-line and prior to the book’s arrival at the binding line. In the most basic case-making, two pieces of cardboard are placed onto a glued piece of cloth with a space between them into which is glued a thinner board cut to the width of the spine of the book. The overlapping edges of the cloth (about 5/8″ all round) are folded over the boards, and pressed down to adhere. After case-making the stack of cases will go to the foil stamping area for adding decorations and type.

Retail and distribution

Main article: Bookselling

Bookselling is the commercial trading of books that forms the retail and distribution end of the publishing process.

Accessible publishing

Main article: Accessible publishingAn example of someone using a screen reader showing documents that are inaccessible, readable and accessible

Accessible publishing is an approach to publishing and book design whereby books and other texts are made available in alternative formats designed to aid or replace the reading process. It is particularly relevant for people who are blind, visually impaired or otherwise print-disabled.

Alternative formats that have been developed to aid different people to read include varieties of larger fonts, specialized fonts for certain kinds of reading disabilities, braille, ebooks, and automated audiobooks and DAISY digital talking books.

Accessible publishing has been made easier through developments in technology such as print on demand, ebook readers, the XML structured data format, the EPUB3 format and the Internet.

Audiobooks

Main article: Audiobook

An audiobook or talking book is a recording of a book or other work being read out loud. A reading of the complete text is described as “unabridged”, while readings of shorter versions are abridgements.

Spoken audio has been available in schools and public libraries and to a lesser extent in music shops since the 1930s. Many spoken word albums were made prior to the age of cassettes, compact discs, and downloadable audio, often of poetry and plays rather than books. It was not until the 1980s that the medium began to attract book retailers, and then book retailers started displaying audiobooks on bookshelves rather than in separate displays.

Ebooks

Main article: Ebook

An ebook (short for electronic book), also spelled e-book or eBook, is a book publication made available in electronic form, consisting of text, images, or both, readable on the flat-panel display of computers or other electronic devices.[38] Although sometimes defined as “an electronic version of a printed book”,[39] some ebooks exist without a printed equivalent. Ebooks can be read on dedicated e-reader devices and on any computer device that features a controllable viewing screen, including desktop computers, laptops, tablets and smartphones.

In some markets, the sale of printed books has decreased due to the increased use of ebooks. However, printed books still largely outsell ebooks, and many people have a preference for print.[40][41][42][43]

Dummy books

Dummy books (or faux books) are books that are designed to imitate a real book by appearance to deceive people, some books may be whole with empty pages, others may be hollow or in other cases, there may be a whole panel carved with spines which are then painted to look like books, titles of some books may also be fictitious.

There are many reasons to have dummy books on display such as; to allude visitors of the vast wealth of information in their possession and to inflate the owner’s appearance of wealth, to conceal something,[44] for shop displays or for decorative purposes.

In early 19th century at Gwrych Castle, North Wales, Lloyd Hesketh Bamford-Hesketh was known for his vast collection of books at his library, however, at the later part of that same century, the public became aware that parts of his library was a fabrication, dummy books were built and then locked behind glass doors to stop people from trying to access them, from this a proverb was born, “Like Hesky’s library, all outside”.[45][46]

Content

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (February 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Libraries, bookstores, and collections commonly divide books into fiction and non-fiction, though other types exist beyond this. Other books, which remain unpublished or are primarily published as part of different business functions (such as phone directories) may not be sold by bookstores or collected by libraries. Manuscripts, logbooks and other records may be classified and stored differently by special collections or archives.

Fiction

Fiction books contain invented material, typically narratives. Other literary forms such as poetry are included in the broad category. Most fiction is additionally categorized by literary form and genre.

The novel is the most common form of fiction book. Novels are extended works of narrative fiction, typically featuring a plot, setting, themes and characters. The novel has had a tremendous impact on entertainment and publishing markets.[47][better source needed] A novella is a term sometimes used for fiction prose typically between 17,500 and 40,000 words, and a novelette between 7,500 and 17,500. A short story may be any length up to 10,000 words, but these word lengths vary.

Comic books or graphic novels are books in which the story is illustrated. The characters and narrators use speech or thought bubbles to express verbal language.

Non-fiction

Non-fiction books are in principle based on fact, encompassing subjects such as history, politics, social and cultural issues, as well as autobiographies and memoirs. Nearly all academic literature is non-fiction.

Reference

Main article: Reference work

Reference books are non-fiction books intended to be quickly referred to for information, rather than read beginning to end. The writing style used in these works is informative; the authors avoid opinions and the use of the first person, and emphasize facts.

An almanac is a very general reference book, usually one-volume, with lists of data and information on many topics. An encyclopedia is a book or set of books designed to have more in-depth articles on many topics. A book listing words, their etymology, meanings, and other information is called a dictionary. An atlas is a book containing a collection of maps. A specialized reference work giving information about a particular field or technique, often intended for professional use, is often called a handbook. Books which try to list references and abstracts in a certain broad area may be called an index, such as Engineering Index, or abstracts such as chemical abstracts and biological abstracts.

Technical

See also: Technical writing

Books with technical information on how to do something or how to use some equipment are called instruction manuals. Other popular how-to books include cookbooks and home improvement books.

Educational

Students often carry textbooks and schoolbooks for study purposes. Lap books are a learning tool created by students. Elementary school pupils often use workbooks, which are published with spaces or blanks to be filled by them for study or homework. In US higher education, it is common for a student to take an exam using a blue book.

Religious

Main article: Religious text

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They often feature a compilation or discussion of beliefs, ritual practices, moral commandments and laws, ethical conduct, spiritual aspirations, and admonitions for fostering a religious community.

Hymnals are books with collections of musical hymns that can typically be found in churches. Prayerbooks or missals are books that contain written prayers and are commonly carried by monks, nuns, and other devoted followers or clergy.

Children’s books

This section is an excerpt from Children’s literature.[edit]

Children’s literature or juvenile literature includes stories, books, magazines, and poems that are created for children. Modern children’s literature is classified in two different ways: genre or the intended age of the reader, from picture books for the very young to young adult fiction.Children’s literature can be traced to traditional stories like fairy tales, which have only been identified as children’s literature since the eighteenth century, and songs, part of a wider oral tradition, which adults shared with children before publishing existed. The development of early children’s literature, before printing was invented, is difficult to trace. Even after printing became widespread, many classic “children’s” tales were originally created for adults and later adapted for a younger audience. Since the fifteenth century much literature has been aimed specifically at children, often with a moral or religious message. Children’s literature has been shaped by religious sources, like Puritan traditions, or by more philosophical and scientific standpoints with the influences of Charles Darwin and John Locke.[48] The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries are known as the “Golden Age of Children’s Literature” because many classic children’s books were published then.

Unpublished

See also: List of unpublished books

Many books are only used to record personal ideas, notes, and accounts, such as notebooks, logbooks, commonplace books, and diaries. These books are rarely published and are typically destroyed or remain private.

Address books, phone books, and calendar/appointment books are commonly used for recording appointments, meetings and personal contact information. Businesses historically used accounting books such as journals and ledgers to record financial data in a practice called bookkeeping (now usually held on computers rather than in hand-written form).

Collection and classification

| This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (August 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) |

Personal and public libraries, archives and other forms of book collection have led to the creation of many different organization and classification strategies. In the 19th and 20th century, libraries and library professionals systematized book collecting and classification systems to respond to the growing industry. The most widely used system is ISBN, which has provided unique identifiers for books since 1970.

Libraries

Main article: Library

A library is a collection of books, and possibly other materials and media, that is accessible for use by its members and members of allied institutions. Libraries provide physical (hard copies) or digital (soft copies) materials, and may be a physical location, a virtual space, or both. A library’s collection normally includes printed materials which may be borrowed, and usually also includes a reference section of publications which may only be utilized inside the premises. Resources such as commercial releases of films, television programs, other video recordings, radio, music and audio recordings may be available in many formats. These include DVDs, Blu-rays, CDs, cassettes, or other applicable formats such as microform. They may also provide access to information, music or other content held on bibliographic databases.

Libraries can vary widely in size and may be organized and maintained by a public body such as a government, an institution (such as a school or museum), a corporation, or a private individual. In addition to providing materials, libraries also provide the services of librarians who are trained experts in finding, selecting, circulating and organising information while interpreting information needs and navigating and analyzing large amounts of information with a variety of resources.

Library buildings often provide quiet areas for studying, as well as common areas for group study and collaboration, and may provide public facilities for access to their electronic resources, such as computers and access to the Internet.

The library’s clientele and general services offered vary depending on its type: users of a public library have different needs from those of a special library or academic library, for example. Libraries may also be community hubs, where programs are made available and people engage in lifelong learning. Modern libraries extend their services beyond the physical walls of the building by providing material accessible by electronic means, including from home via the Internet.

Identification and classification

In 2011, the International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA) created the International Standard Bibliographic Description (ISBD) in order to standardize descriptions in bibliographies and library catalogs. Each book is specified by an International Standard Book Number, or ISBN, which is meant to be unique to every edition of every book produced by participating publishers, worldwide. It is managed by the ISBN Society. An ISBN has four parts: the first part is the country code, the second the publisher code, and the third the title code. The last part is a check digit, and can take values from 0–9 and X (10). The EAN Barcodes numbers for books are derived from the ISBN by prefixing 978, for Bookland, and calculating a new check digit.

Commercial publishers in industrialized countries generally assign ISBNs to their books, so buyers may presume that the ISBN is part of a total international system, with no exceptions. However, many government publishers, in industrial as well as developing countries, do not participate fully in the ISBN system, and publish books which do not have ISBNs. A large or public collection requires a catalogue. Codes called “call numbers” relate the books to the catalogue, and determine their locations on the shelves. Call numbers are based on a Library classification system. The call number is placed on the spine of the book, normally a short distance before the bottom, and inside. Institutional or national standards, such as ANSI/NISO Z39.41 – 1997, establish the correct way to place information (such as the title, or the name of the author) on book spines, and on “shelvable” book-like objects, such as containers for DVDs, video tapes and software.

One of the earliest and most widely known systems of cataloguing books is the Dewey Decimal System. Another widely known system is the Library of Congress Classification system. Both systems are biased towards subjects which were well represented in US libraries when they were developed, and hence have problems handling new subjects, such as computing, or subjects relating to other cultures.[49] Information about books and authors can be stored in databases like online general-interest book databases. Metadata, which means “data about data” is information about a book. Metadata about a book may include its title, ISBN or other classification number (see above), the names of contributors (author, editor, illustrator) and publisher, its date and size, the language of the text, its subject matter, etc.

Classification systems

- Bliss bibliographic classification (BC)

- Chinese Library Classification (CLC)

- Colon Classification

- Dewey Decimal Classification (DDC)

- Harvard-Yenching Classification

- Library of Congress Classification (LCC)

- New Classification Scheme for Chinese Libraries

- Universal Decimal Classification (UDC)

Conservation

The conservation and restoration of books, manuscripts, documents, and ephemera is dedicated to extending the life of items of historical and personal value made primarily from paper, parchment, and leather. When applied to cultural heritage, conservation activities are generally undertaken by a conservator. The primary goal of conservation is to extend the lifespan of the object as well as maintaining its integrity by keeping all additions reversible. Conservation of books and paper involves techniques of bookbinding, restoration, paper chemistry, and other material technologies including preservation and archival techniques.[50]

Book and paper conservation seeks to prevent and, in some cases, reverse damage due to handling, inherent vice, and the environment.[51][52] Conservators determine proper methods of storage for books and documents, including boxes and shelving to prevent further damage and promote long term storage.[53] Carefully chosen methods and techniques of active conservation can both reverse damage and prevent further damage in batches or single-item treatments based on the value of the book or document.[54]

Historically, book restoration techniques were less formalized and carried out by various roles and training backgrounds. Nowadays, the conservation of paper documents and books is often performed by a professional conservator.[52][55] Many paper or book conservators are members of a professional body, such as the American Institute for Conservation (AIC) or the Guild of Bookworkers (both in the United States), the Archives and Records Association (in the United Kingdom and Ireland), or the Institute of Conservation (ICON) (in the United Kingdom).[56]

Social and cultural issues

Reception

Main article: Literary criticism

The impact of books can be various, and record of that reception comes in several formats: starting with initial public reception in contemporary newspapers, pop culture and correspondence, and then developing with different forms of literary criticism by professional and academic critics. For the publishing industry the “book review” is an important part of increasing awareness and reception of a book: able to make or break the public opinion about a new book.[citation needed]

Book reviews

This section is an excerpt from Book review.[edit]

A book review is a form of literary criticism in which a book is merely described (summary review) or analyzed based on content, style, and merit.[57]

A book review may be a primary source, an opinion piece, a summary review, or a scholarly view.[58] Books can be reviewed for printed periodicals, magazines, and newspapers, as school work, or for book websites on the Internet. A book review’s length may vary from a single paragraph to a substantial essay. Such a review may evaluate the book based on personal taste. Reviewers may use the occasion of a book review for an extended essay that can be closely or loosely related to the subject of the book, or to promulgate their ideas on the topic of a fiction or non-fiction work.Some journals are devoted to book reviews, and reviews are indexed in databases such as the Book Review Index and Kirkus Reviews; but many more book reviews can be found in newspaper and scholarly databases such as Arts and Humanities Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, and discipline-specific databases.

Book censorship and bans

Book censorship is the act of some authority taking measures to suppress ideas and information within a book.[59] Censorship is “the regulation of free speech and other forms of entrenched authority”.[60] Censors typically identify as either a concerned parent, community members who react to a text without reading, or local or national organizations.[61] Books have been censored by authoritarian dictatorships to silence dissent, such as the People’s Republic of China, Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. Books are most often censored for age appropriateness, offensive language, sexual content, amongst other reasons.[62] Similarly, religions may issue lists of banned books, such as the historical example of the Catholic Church‘s Index Librorum Prohibitorum and bans of such books as Salman Rushdie’s The Satanic Verses by Ayatollah Khomeini,[63] which do not always carry legal force. Censorship can be enacted at the national or subnational level as well, and can carry legal penalties. In many cases, the authors of these books could face harsh sentences, exile from the country, or even execution.[64][65]

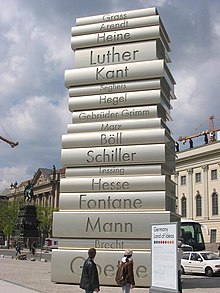

Book burning

This section is an excerpt from Book burning.[edit]

Book burning is the deliberate destruction by fire of books or other written materials, usually carried out in a public context. The burning of books represents an element of censorship and usually proceeds from a cultural, religious, or political opposition to the materials in question.[66] Book burning can be an act of contempt for the book’s contents or author, intended to draw wider public attention to this opposition, or conceal the information contained in the text from being made public, such as diaries or ledgers. Burning and other methods of destruction are together known as biblioclasm or libricide.

In some cases, the destroyed works are irreplaceable and their burning constitutes a severe loss to cultural heritage. Examples include the burning of books and burying of scholars under China’s Qin dynasty (213–210 BCE), the destruction of the House of Wisdom during the Mongol siege of Baghdad (1258), the destruction of Aztec codices by Itzcoatl (1430s), the burning of Maya codices on the order of bishop Diego de Landa (1562),[67] and the burning of Jaffna Public Library in Sri Lanka (1981).[68]In other cases, such as the Nazi book burnings, copies of the destroyed books survive, but the instance of book burning becomes emblematic of a harsh and oppressive regime which is seeking to censor or silence some aspect of prevailing culture.